Bravo Zulu is naval signal code for “manoeuvre well executed” or “job well done” and Tian Fu is the name of the 38,000 tonne general cargo ship that rescued British round-the-world sailor Susie Goodall in the South Pacific this weekend.

Like many, I have been following the story ever since Susie’s 35ft yacht, DHL Starlight was dismasted last Wednesday in 75mph winds and waves of 9m+. Dismasted not after just being rolled and capsizing but dismasted after surfing down the crest of a wave and being flipped end-over-end, stern over bow. At the time she was 4th in the Golden Globe race and about 2000 miles west of Cape Horn. It’s been quite a year for the Golden Globe (see Blog 23: The weather theme continued …. but spare a thought and prayer this Sunday for Abhilash Tomy, 23 Sep) and quite a year for women skippers! (See Blog 14: Girl Power!, 2 Aug). The arrival on scene of the Hong-Kong registered Tian Fu was not the end of the excitement as Susie then had to stand on the ruined hull of DHL Starlight and judge the right time to hook-on to the safety line winched down to her from the cargo vessel.

Perhaps not quite as bad as being flipped stern over bow but not without its challenges! Its enough to put some people off sailing…………… it certainly puts sea survival into perspective (see Blog 28: Level 2 Training Part 1. Sea Survival, 25 Oct) ……. and any of my own concerns pale into complete insignificance. For example …..

This time next year (give or take a week or so for artistic licence) I will be at a Board meeting of the Harwich Harbour Authority. One of the trickiest decisions I always face at such meetings is where to sit. Or perhaps not where exactly but rather which way to face. The CEO’s office, when doubling as the Board Room, offers spectacular views of part of the HHA ‘patch’.

Off to the left the river Stour leads up to Harwich International Port

and, further up stream, the small picturesque port of Mistley.

Looking directly ahead from the conference room is the confluence of the river Stour and the River Orwell and the view across the water towards Shotley.

Off to the right the river Stour leads 20 miles or so up to the port of Ipswich, passing sites of special scientific interest and a number of other yacht marinas. Generally speaking there is ALWAYS something to see which is something of a distraction to some (for “some” read “most”) of us – hence the tricky “where to sit decision.”

Next year I think it might be even harder. This time next year (slight crossing of fingers on my none typing hand) I will have completed my Clipper adventure for 2019 and will be back from Western Australia. Depending on how quickly or not we actually race I may only be just back, quite literally hanging my Musto smock up, as I open my laptop (paperless Board meetings 😉)

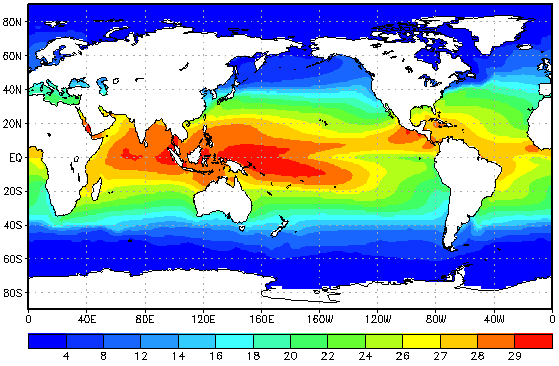

Leg2, the South Atlantic Challenge is roughly 3,560 nautical miles and is “programmed” to take 17-18 days. In the last race the leg was won by Greenings in 14 days, 1 hour and 50 minutes and the highest yacht speed on the leg was recorded as 30.9 knots! Not surprisingly, the South Atlantic Challenge is described as one for the thrill-seekers. On leaving South American waters teams encounter the Trade Winds and the long rolling swells of the South Atlantic towards South Africa.

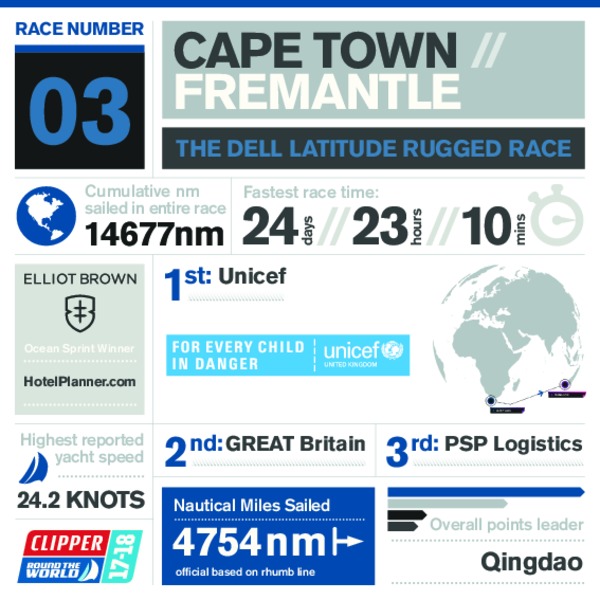

Leg 3, the Southern Ocean Leg, also known as the Southern Ocean Sleigh Ride, is 4,754 nautical miles long, normally between Cape Town, South Africa and Freemantle, Western Australia. It is “programmed” for 23-24 days racing and in the last race the leg was won by Unicef in 24 days, 23 hours and 10 minutes. The highest reported yacht speed was 24.2 knots. This leg offers some of the most exhilarating and testing conditions of the entire circumnavigation, perhaps second only to Leg 6, the Mighty Pacific. On this leg we will dip into the notoriously strong winds of the Roaring Forties, which lie between 40 and 50 degrees south. Once clear of the stunning but fickle-winded Table Bay, the race will head for the first Great Cape – The Cape of Good Hope, and on to the Agulhas Bank, an area notorious for very disturbed seas where the Atlantic and Indian Oceans meet. Despite the gruelling reputation that the Roaring Forties command – we will be surfing downwind on some swells higher than buildings – this is a place respected by sailors world wide as one of the best places to fully appreciate Mother Nature in her most raw and powerful glory.

Put that way is can seem hard enough, but it can be harder than that. At the beginning of the last Leg 2, PSP Logistics collided with a whale that caused damage to the starboard rudder that necessitated a return to Uruguay. The delay caused by the subsequent repairs meant that by the time PSP Logistics rejoined the race the leaders were already approaching half way to Cape Town. And as if that was not enough, at the beginning of Leg 3, Greenings ran aground off the coast of South Africa and, while all the crew were evacuated safely, the yacht was subsequently declared a complete loss.

So, this time next year ………..

On the current “Board forward look” we already have four decision papers to review this time next year. I think I’ll be sitting facing away from the sea view!

![IMG-20180412-WA0014[21656] IMG-20180412-WA0014[21656]](https://i0.wp.com/keithsclipperadventure.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/img-20180412-wa001421656.jpg?w=351&h=263&ssl=1)

cemeteries and there are some 2,500 Commonwealth War Cemeteries worldwide. In each of these cemeteries headstones inscribed simply “A soldier known unto God” mark the final resting places of those who could not be identified. The huge monuments at the Menin Gate and at Thiepval list the 55,000 and 72,000 British and Commonwealth troops who have no known graves from the battles around Ypres and on the Somme respectively in The Great War. It is often surprising to come across sailors at some of these sites so far from the sea but the Royal Navy provided a Division, some 10,000 men, who saw action on the Western Front in the First World War, including during the battles on The Somme and at Passchendaele.

cemeteries and there are some 2,500 Commonwealth War Cemeteries worldwide. In each of these cemeteries headstones inscribed simply “A soldier known unto God” mark the final resting places of those who could not be identified. The huge monuments at the Menin Gate and at Thiepval list the 55,000 and 72,000 British and Commonwealth troops who have no known graves from the battles around Ypres and on the Somme respectively in The Great War. It is often surprising to come across sailors at some of these sites so far from the sea but the Royal Navy provided a Division, some 10,000 men, who saw action on the Western Front in the First World War, including during the battles on The Somme and at Passchendaele.

Services where such wreaths are laid on the site of a wreck of a ship with the same name are particularly moving. Ships operating in the South China Sea nearly always divert to hold Remembrance services over the wrecks of HMShips Prince of Wales and Repulse, the final resting place of over 800 officers and men killed in 1941. Both wrecks, upside down in about 65m of water, have buoys and wires fixed to their propeller shafts to which large white ensigns are attached and regularly replaced, beneath the surface of the sea.

Services where such wreaths are laid on the site of a wreck of a ship with the same name are particularly moving. Ships operating in the South China Sea nearly always divert to hold Remembrance services over the wrecks of HMShips Prince of Wales and Repulse, the final resting place of over 800 officers and men killed in 1941. Both wrecks, upside down in about 65m of water, have buoys and wires fixed to their propeller shafts to which large white ensigns are attached and regularly replaced, beneath the surface of the sea.

in) the size of the mainsail, the “outhaul” (a rope that is used to control the shape of the curve of the foot of the sail) and the “topping lift” (a rope that applies upward force on a boom used primarily to hold the boom up when the sail is lowered) – pretty much everything comes into the snake pit. All are generally different colours and most come through “clutches” (provided for some lines to grip under tension by means of a lever and cam, which enables winches to be freed for other purposes) and a “jammer” each of which is, generally, labelled. Ok so far so good. After a little experience it IS possible

in) the size of the mainsail, the “outhaul” (a rope that is used to control the shape of the curve of the foot of the sail) and the “topping lift” (a rope that applies upward force on a boom used primarily to hold the boom up when the sail is lowered) – pretty much everything comes into the snake pit. All are generally different colours and most come through “clutches” (provided for some lines to grip under tension by means of a lever and cam, which enables winches to be freed for other purposes) and a “jammer” each of which is, generally, labelled. Ok so far so good. After a little experience it IS possible

when making a new tack between the mast and the boom during the reefing of the Mainsail. It follows that when “shaking out the Reef” and re-hoisting the Main that the handy billy must be released by “spiking” the release mechanism by use of a marlin spike (or similar) kept in the snake pit.

when making a new tack between the mast and the boom during the reefing of the Mainsail. It follows that when “shaking out the Reef” and re-hoisting the Main that the handy billy must be released by “spiking” the release mechanism by use of a marlin spike (or similar) kept in the snake pit.

meant my battery had packed in. I don’t remember the last time it happened, but watchkeeping ……….. without a watch …………. adds a certain je ne said quoi to waking in the dark of a pitching yacht, woken by some strange noise or sudden lurch, and NOT knowing what time it is, not knowing how much longer you have until your opposite watch will wake you from your interrupted slumber, and not knowing how much more sleep you might get if you managed to get straight back to sleep. It makes remembering to make hourly log book entries that little bit more difficult too. Somewhat un-nerving at the start it did, eventually, become rather liberating. Time becomes defined by changes in the light as the sun sinks or rises; by meal “times” even when whole-crew yacht evolutions make lunch something of a moveable feast. Sleep, eat, sail, repeat. Maybe I should try it more often? Or maybe I should quit trying to be philosophical and just go out and buy a new watch battery 😉.

meant my battery had packed in. I don’t remember the last time it happened, but watchkeeping ……….. without a watch …………. adds a certain je ne said quoi to waking in the dark of a pitching yacht, woken by some strange noise or sudden lurch, and NOT knowing what time it is, not knowing how much longer you have until your opposite watch will wake you from your interrupted slumber, and not knowing how much more sleep you might get if you managed to get straight back to sleep. It makes remembering to make hourly log book entries that little bit more difficult too. Somewhat un-nerving at the start it did, eventually, become rather liberating. Time becomes defined by changes in the light as the sun sinks or rises; by meal “times” even when whole-crew yacht evolutions make lunch something of a moveable feast. Sleep, eat, sail, repeat. Maybe I should try it more often? Or maybe I should quit trying to be philosophical and just go out and buy a new watch battery 😉.

2017-2018 Round The World Race. During Leg 4 around Australia, Qingdao was hit by lightning during a 40knot Southerly Buster (violent squall) and still finished 5th on arrival in the Whitsundays. Chris and his crew achieved 4 podium finishes: 3rd into Sydney, 3rd on arrival into Sanya, 1st across the North Pacific into Seattle and 1st in the final race from Derry-Londonderry to Liverpool. Qingdao finished 3rd overall with 135 points, only 4 points behind Visit Seattle in 2nd (139 points) and only 8 points behind the winners Sanya Serenity Coast (143 points). In his profile interview for Clipper ahead of the previous race, in answer to the question, “what’s your favourite word?” Chris replied:

2017-2018 Round The World Race. During Leg 4 around Australia, Qingdao was hit by lightning during a 40knot Southerly Buster (violent squall) and still finished 5th on arrival in the Whitsundays. Chris and his crew achieved 4 podium finishes: 3rd into Sydney, 3rd on arrival into Sanya, 1st across the North Pacific into Seattle and 1st in the final race from Derry-Londonderry to Liverpool. Qingdao finished 3rd overall with 135 points, only 4 points behind Visit Seattle in 2nd (139 points) and only 8 points behind the winners Sanya Serenity Coast (143 points). In his profile interview for Clipper ahead of the previous race, in answer to the question, “what’s your favourite word?” Chris replied:

We (21 of us in total) started the Saturday morning at Brune Park School in Gosport for

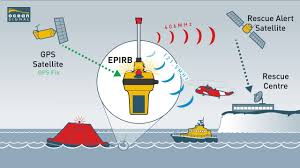

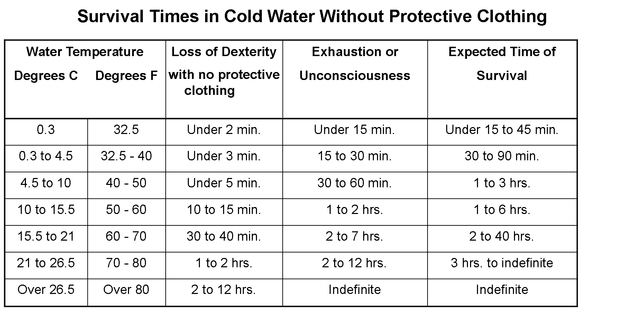

We (21 of us in total) started the Saturday morning at Brune Park School in Gosport for  the Clipper version of the RYA Sea Survival Course. It had been about 12 years since I last did a Sea Survival Course and Brune Park School swimming pool was a vast improvement on Horsea Lake. The first half of the day was in the classroom looking at just about everything that could go wrong (fires, floods, collisions, heavy weather, man over boards, catastrophic sinking, cold water shock, hypothermia, frostbite, sea sickness, starvation, dehydration etc etc – all good morale boosting stuff!) and various chances of survival (or otherwise) plus a vast array of equipment and techniques

the Clipper version of the RYA Sea Survival Course. It had been about 12 years since I last did a Sea Survival Course and Brune Park School swimming pool was a vast improvement on Horsea Lake. The first half of the day was in the classroom looking at just about everything that could go wrong (fires, floods, collisions, heavy weather, man over boards, catastrophic sinking, cold water shock, hypothermia, frostbite, sea sickness, starvation, dehydration etc etc – all good morale boosting stuff!) and various chances of survival (or otherwise) plus a vast array of equipment and techniques  all designed to make survival/rescue a realistic possibility (warm clothing, waterproofs, dry suits, abandoning ship controlled, abandoning ship catastrophic, EPIRB – Emergency Position Indicating Radio Beacon, SART – Search and Rescue Radar Transponder, flares, life jackets, spray hoods, life rafts and what to take with you, food rationing, water rationing, first aid etc etc). Top tip – only leave the yacht as a last resort, usually only AS it sinks or if it catches fire and you can’t put the damn thing out. Take the EPIRB with you if you abandon the yacht but if there is no time, and the yacht sinks quickly then Clipper EPIRBs, like Clipper life rafts, have hydrostatic releases which will “fire” as the yacht sinks (normally at depths of between 1 and 4 metres or 3 to 13 feet) 🙂

all designed to make survival/rescue a realistic possibility (warm clothing, waterproofs, dry suits, abandoning ship controlled, abandoning ship catastrophic, EPIRB – Emergency Position Indicating Radio Beacon, SART – Search and Rescue Radar Transponder, flares, life jackets, spray hoods, life rafts and what to take with you, food rationing, water rationing, first aid etc etc). Top tip – only leave the yacht as a last resort, usually only AS it sinks or if it catches fire and you can’t put the damn thing out. Take the EPIRB with you if you abandon the yacht but if there is no time, and the yacht sinks quickly then Clipper EPIRBs, like Clipper life rafts, have hydrostatic releases which will “fire” as the yacht sinks (normally at depths of between 1 and 4 metres or 3 to 13 feet) 🙂

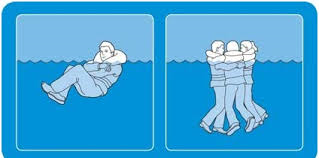

practiced a floating-feet together-group-huddle. And then finally we got to go boating – or rather rafting. Life rafting. 10 or so of us in an 8 man life raft was certainly cosy – and very warm very quickly – and we practised lookouts, baling, rigging and steering by drogues. We also practiced, individually, righting a capsized life raft by pulling it over our head, remembering at the vital moment to raise a fist to punch the floor as it drops on top of you so as to create an air pocket in which you can breath and thus orientate yourself to escape. Life rafts have large stability pockets that hang down beneath them and fluorescent strips on the underside to indicate escape routes to avoid entanglement in these pockets. It pays to orientate yourself before trying to get to the surface. It would be doubly ironic to drown UNDER a life raft!

practiced a floating-feet together-group-huddle. And then finally we got to go boating – or rather rafting. Life rafting. 10 or so of us in an 8 man life raft was certainly cosy – and very warm very quickly – and we practised lookouts, baling, rigging and steering by drogues. We also practiced, individually, righting a capsized life raft by pulling it over our head, remembering at the vital moment to raise a fist to punch the floor as it drops on top of you so as to create an air pocket in which you can breath and thus orientate yourself to escape. Life rafts have large stability pockets that hang down beneath them and fluorescent strips on the underside to indicate escape routes to avoid entanglement in these pockets. It pays to orientate yourself before trying to get to the surface. It would be doubly ironic to drown UNDER a life raft!

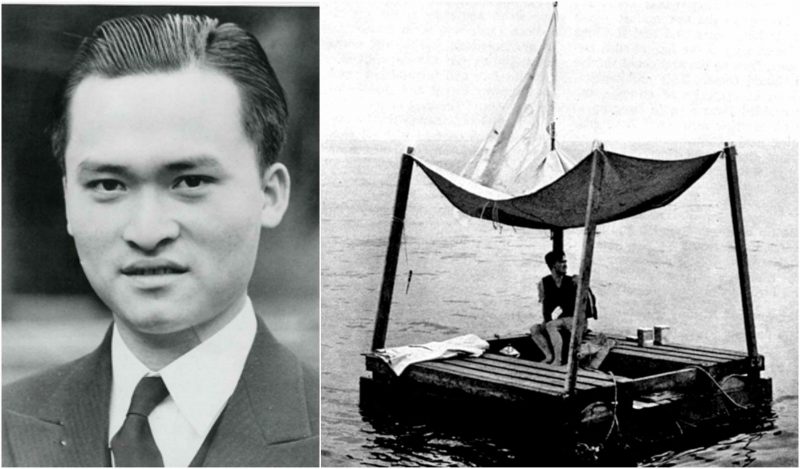

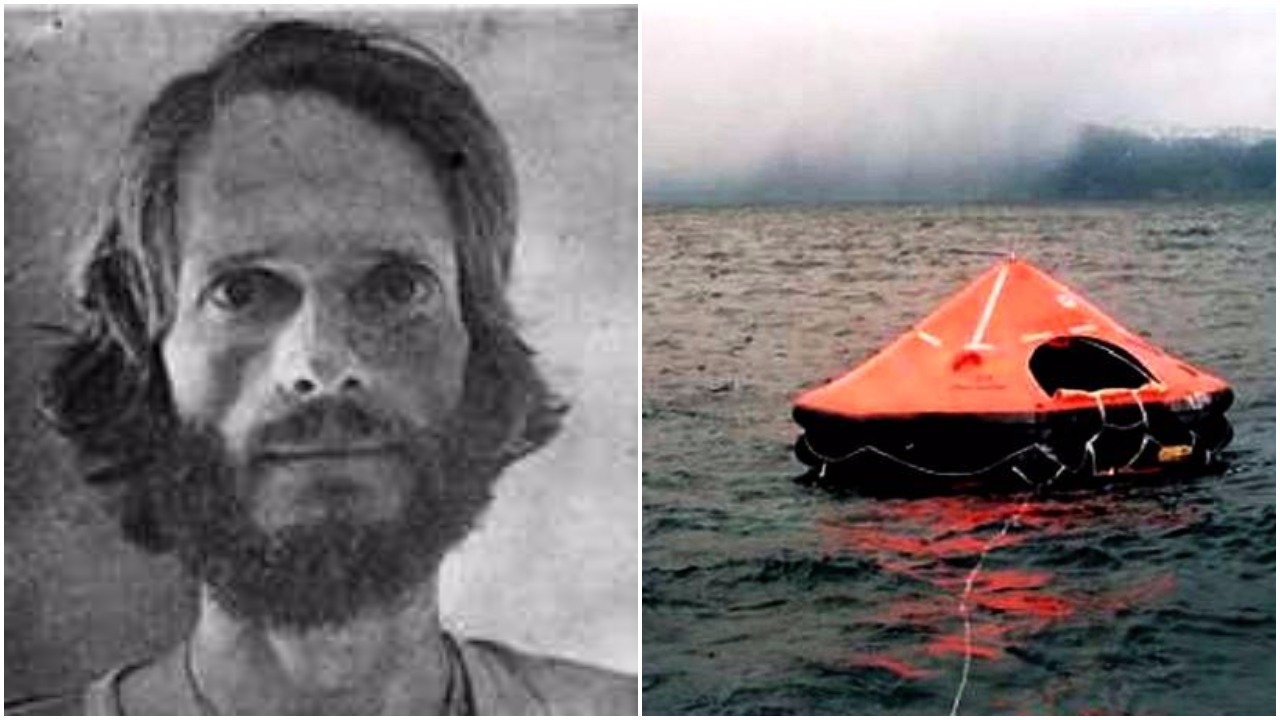

was torpedoed in the South Atlantic on 23rd November 1942. The ship sank in 2 minutes. After 2 hours in the water Lim found and climbed on to a 8ft square wooden raft. The raft had several tins of biscuits, a 40 litre jug of water, some chocolate, a bag of sugar lumps, some flares, two smoke pots and a torch. After his ordeal (he was rescued by Brazilian fishermen as he drifted near the coast of Brazil), he was awarded the British Empire Medal and after the war he emigrated to the United States. He died in Brooklyn in 1991 at the age of 72.

was torpedoed in the South Atlantic on 23rd November 1942. The ship sank in 2 minutes. After 2 hours in the water Lim found and climbed on to a 8ft square wooden raft. The raft had several tins of biscuits, a 40 litre jug of water, some chocolate, a bag of sugar lumps, some flares, two smoke pots and a torch. After his ordeal (he was rescued by Brazilian fishermen as he drifted near the coast of Brazil), he was awarded the British Empire Medal and after the war he emigrated to the United States. He died in Brooklyn in 1991 at the age of 72. Lucette, sank after being holed by a pod of killer whales 200 miles west of the Galapagos Islands in the Pacific. Dougal Robertson told the story of their survival in the book The Last Voyage of the Lucette (with a forward by Sir Robin Knox Johnson). Also see

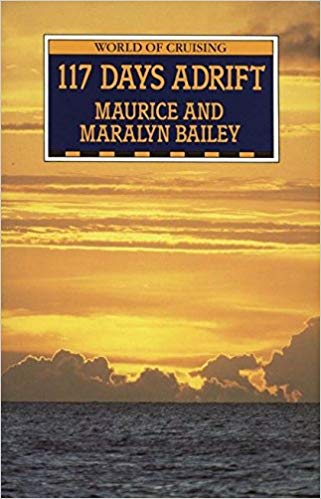

Lucette, sank after being holed by a pod of killer whales 200 miles west of the Galapagos Islands in the Pacific. Dougal Robertson told the story of their survival in the book The Last Voyage of the Lucette (with a forward by Sir Robin Knox Johnson). Also see  1973. Their journey began from Southampton and their intended destination was New Zealand. They passed safely through the Panama Canal in February but were struck by a whale at dawn on 4th March. They managed to salvage some supplies, some food and a compass and transfer them to an inflated life raft and a dingy before Auralyn foundered. After drifting some 1,500 miles they were rescued by the crew of a South Korean fishing boat on 30th June and were brought onboard in an emaciated state. They recounted their story in the book 117 Days Adrift, published in 1974 and, the following year, they returned to sea in their new yacht, Auralyn II.

1973. Their journey began from Southampton and their intended destination was New Zealand. They passed safely through the Panama Canal in February but were struck by a whale at dawn on 4th March. They managed to salvage some supplies, some food and a compass and transfer them to an inflated life raft and a dingy before Auralyn foundered. After drifting some 1,500 miles they were rescued by the crew of a South Korean fishing boat on 30th June and were brought onboard in an emaciated state. They recounted their story in the book 117 Days Adrift, published in 1974 and, the following year, they returned to sea in their new yacht, Auralyn II. John Glennie, Rick Hellriegel, Phil Hoffman and James Nalepka survived 119 days on the upturned hull of their catamaran Rose Noelle in 1989, when it capsized in the southern Pacific off New Zealand after being hit by a rogue wave. Glennie and Nalepka both wrote books about their ordeal and their story was told in a 2015 New Zealand television film, Abandoned. The other crew admitted they came close to killing Glennie, blaming him for getting them into trouble in the first place!

John Glennie, Rick Hellriegel, Phil Hoffman and James Nalepka survived 119 days on the upturned hull of their catamaran Rose Noelle in 1989, when it capsized in the southern Pacific off New Zealand after being hit by a rogue wave. Glennie and Nalepka both wrote books about their ordeal and their story was told in a 2015 New Zealand television film, Abandoned. The other crew admitted they came close to killing Glennie, blaming him for getting them into trouble in the first place! night storm and became swamped. In his book, Adrift: 76 Days Lost At Sea, Callahan writes that he suspects the damage was caused by a collision with ………………. yes, you guessed it………….…. a whale. Callahan escaped into a 6 man life raft and managed to retrieve a number of essential items including a sleeping bag, some food, charts, a short spear gun, flares, torch, solar stills for producing drinking water and a copy of Sea Survival, a survival manual written by ……………… Dougal Robertson of Lucette fame! Having survived on mahi-mahi, triggerfish (which he speared), flying fish, barnacles and birds that he caught, and using his stills, and captured rain water, to produce up to a pint

night storm and became swamped. In his book, Adrift: 76 Days Lost At Sea, Callahan writes that he suspects the damage was caused by a collision with ………………. yes, you guessed it………….…. a whale. Callahan escaped into a 6 man life raft and managed to retrieve a number of essential items including a sleeping bag, some food, charts, a short spear gun, flares, torch, solar stills for producing drinking water and a copy of Sea Survival, a survival manual written by ……………… Dougal Robertson of Lucette fame! Having survived on mahi-mahi, triggerfish (which he speared), flying fish, barnacles and birds that he caught, and using his stills, and captured rain water, to produce up to a pint  of water a day, he drifted for some 1,800 miles and across at least two shipping lanes (he spotted 9 ships) without rescue. On the evening of 20th April 1982 he spotted the lights of an island south east of Guadeloupe and was rescued by local fishermen the next day. During the ordeal he faced sharks, raft punctures, equipment deterioration, physical deterioration and mental stress. He lost a third of his body weight and was covered with scores of saltwater sores. He described seeing the night sky at one point as “a view of heaven from a seat in hell” and still enjoys sailing and the sea, which he calls the world’s greatest wilderness.

of water a day, he drifted for some 1,800 miles and across at least two shipping lanes (he spotted 9 ships) without rescue. On the evening of 20th April 1982 he spotted the lights of an island south east of Guadeloupe and was rescued by local fishermen the next day. During the ordeal he faced sharks, raft punctures, equipment deterioration, physical deterioration and mental stress. He lost a third of his body weight and was covered with scores of saltwater sores. He described seeing the night sky at one point as “a view of heaven from a seat in hell” and still enjoys sailing and the sea, which he calls the world’s greatest wilderness.